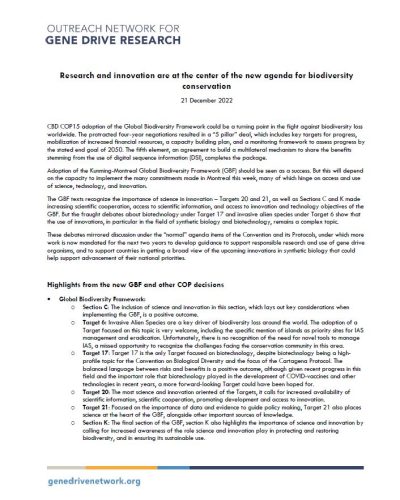

Why does gene drive research matter?

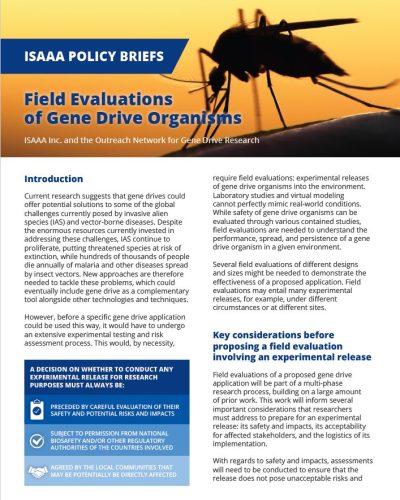

Gene drive approaches could offer complementary, sustainable and scalable strategies to control the transmission of vector-borne diseases and the population of invasive alien species that threaten native ecosystems. Both vector-borne diseases and invasive alien species are complex issues that existing strategies and tools have not been able to fully address to date. Their burden for society is enormous in terms of health, economic and social costs, underscoring the critical need for research into novel approaches.

17%

of the estimated global burden of communicable diseases are major vector-borne diseases.

700

THOUSAND

lives are claimed by vector-borne diseases every year.

$12B

is estimated to be spent on malaria direct costs per year.

5%

of the earth’s land surface is covered by islands yet they are home to nearly half of all endangered species.

60%

of recorded extinctions worldwide and 90% of recorded extinctions on islands are associated with invasive alien species.

$423B

is the estimated annual economic cost of invasive alien species.

Resources