Horseshoe crabs are often described as “living fossils.” They have roamed our planet’s coastal waters for over 445 million years, predating even the dinosaurs. With a helmet-like shell, pointed tail, ten eyes and six pairs of legs, their appearance is strikingly prehistoric. Despite their name, horseshoe crabs are not true crabs, but marine arthropods more closely related to spiders, ticks and scorpions. They are a keystone species playing a vital role in maintaining the health of estuarine and coastal ecosystems.

Yet every year, more than a million horseshoe crabs are harvested for a chemical in their blood called Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL), which plays a crucial role in testing vaccines and injectable medications to ensure they are safe for humans.

Horseshoe crabs mating along Chesapeake Bay, US, at dawn.

Because LAL is so effective, pharmaceutical companies have relied on it for decades. While efforts are made to return the horseshoe crabs to the sea, it is estimated that 15% do not survive the process. In Asia, where similar tests are performed using local species, the crabs are usually not returned at all, and instead are sold for human consumption.

This reliance has come at a price, with horseshoe crabs now facing precipitous declines in their numbers, as a result of biomedical testing, combined with overharvesting of the species for use as food and bait, and additional pressures brought on by habitat loss and climate impacts. The Asian tri-spine horseshoe crab, one of four existing horseshoe crab species, is classified as “Endangered” according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The American horseshoe crab is listed as “Vulnerable” and the two additional Asian horseshoe crab species are expected to soon be listed on the IUCN Red List.

Atlantic horseshoe crabs are found on the U.S. coastline from New England to Florida and in Mexico.

To eliminate our reliance on the blood of these ancient creatures, scientists have been exploring synthetic alternatives. An example comes in the form of a laboratory-made protein, called Recombinant Factor C (rFC), which mimics the LAL reaction by using cloned DNA from horseshoe crabs. Studies have demonstrated that rFC-based tests are comparable to LAL. Although adoption of synthetic alternatives has been slow, recent changes in medical regulations are raising hope that the practice of horseshoe crab bleeding could be replaced with the use of these effective alternatives. As of May 2025, the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) officially recognizes synthetic alternatives to the blood of horseshoe crabs as effective and safe for detecting bacterial endotoxins (contaminants) in injectable drugs and vaccines.

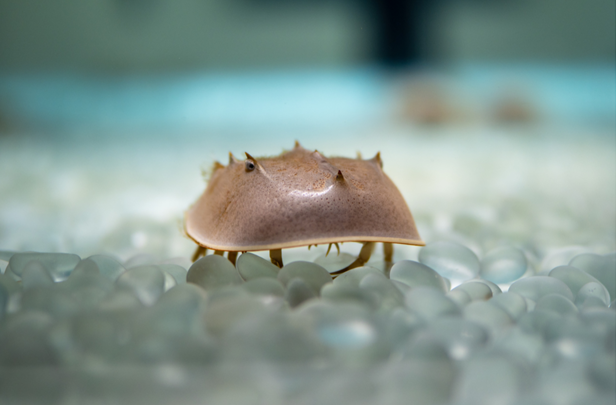

Horseshoe crabs walk on 10 legs and use their last pair, called the chelicera, to move food into their mouths.

Because horseshoe crabs are critical species for coastal biodiversity, their decline has wider ecological consequences. During the warmer months of the year, especially at night during the full and new moons, horseshoe crabs emerge from the sea to spawn. They lay millions of eggs on beaches – a food source for shorebirds, fish and other wildlife.

Shorebirds, like the threatened Red Knot, a migratory bird that travels from the southern tip of South America to the Arctic each year, rely on them for feeding. In Delaware Bay, USA, Red Knots feed almost exclusively on horseshoe crab eggs to double their weight before continuing north. The decline in horseshoe crab populations has been linked to decreasing Red Knot populations. Horseshoe crabs also help aerate and fertilize coastal sediments as they burrow and spawn, supporting biodiversity in mudflats and estuaries. Their shells even serve as microhabitats for many species including mussels and sea snails.

Horseshoe crabs swarm the shores of Delaware Bay in a remarkable spawning event. Video: Deep Look.

Reducing the need to harvest horseshoe crabs for medical testing would not only spare hundreds of thousands of crabs from being bled every year, but it could also allow their populations to recover – in turn strengthening coastal environments.

Horseshoe crabs are an ancient and ecologically critical species. For decades, they have safeguarded human health through their unique biology. Coupled with the conservation and restoration of essential spawning and nursery habitats, adopting synthetic alternatives to horseshoe crab blood could mark a turning point, offering hope for horseshoe crab conservation and the preservation of ecosystems that rely on them.